Preface:

During my years as a middle school teacher I assigned many essays for my students to write. Often times I had to confront my students’ unyielding belief that writing was very difficult. With every group of students that complained about the chore of writing, I was moved to relate to them that I, too, once believed that writing, good writing, was not an easy task to accomplish. I related to them that I was a sophomore in college when I last voiced similar misgivings like those that they were mounting in my class. My English professor at that time was Dr. Louis Sheets. I remember complaining to him about the same feelings I was receiving from them. I was told in a matter of fact manner that writing really was not so difficult. “The difficulty,” I was told, “was not in the writing but in the thinking. If your are having a difficult time writing your essay then you most likely do not have clarity of thought. Writing, good writing, requires clarity of thought. Once your thoughts are clear, the words come more easily.”

Requiring students to write essays and term papers places the students in a position where they must demonstrate knowledge of the principles and concepts presented to them but also requires those students to show how, or if, those principles and concepts are integrated into the their worldviews. Clarity of thought is not merely the regurgitation of the facts and opinions presented to be remembered but also the affects that those principles and concepts have on the students’ lives, their behaviors, their opinions and their character, etcetera.

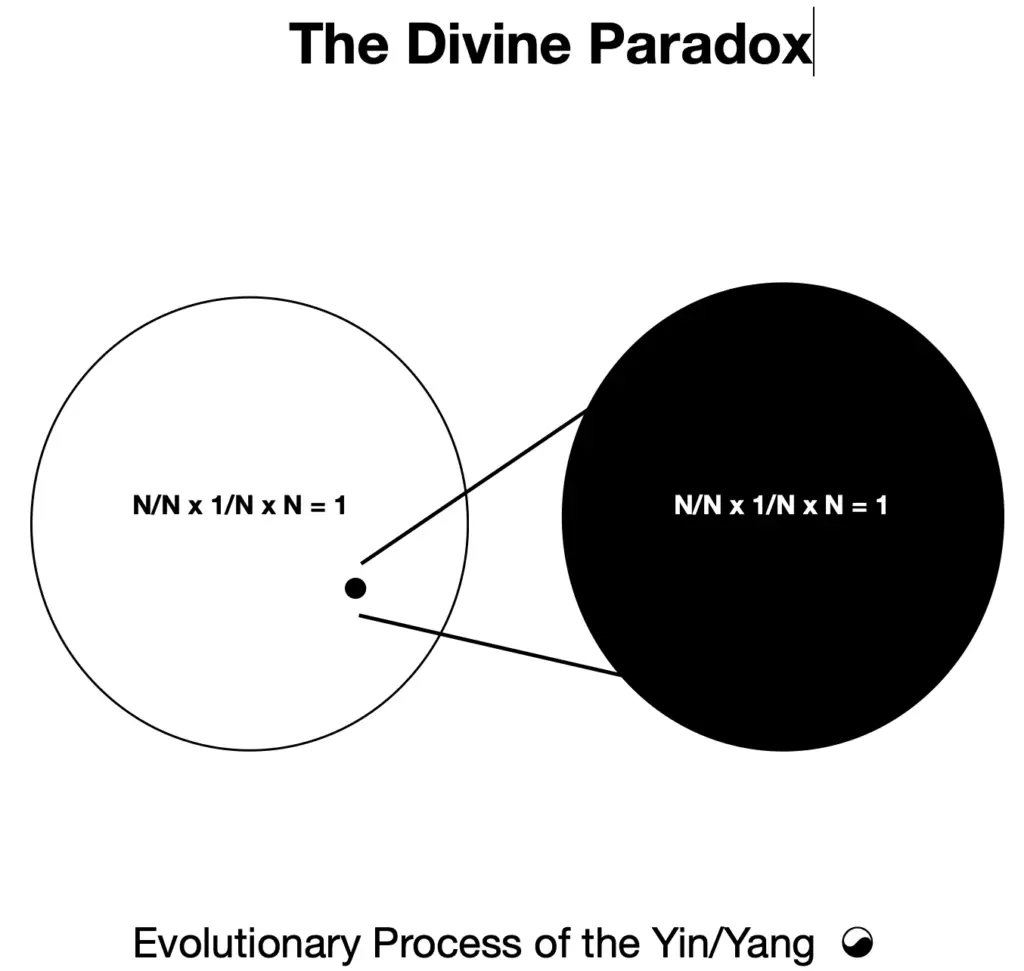

The journey to completing One Bipedal Journey began in late 1968 or early 1969 with my writing the three abstract parables: The Master, The Master Pronoun and Two, and Breathing. My journey started with my coming to terms with the Trinity which, for a Roman Catholic, is coming to terms with God. The Divine Paradox, composed in 2020, comes full circle because it, too, is a coming to terms with my understanding of The Great Spirit of The Universe. My clarity of thought for this One Bipedal Journey took 52 years to crystalize into the graphic, The Divine Paradox. The Divine Paradox is an extension of my resolution of a religious dilemma posed to me while attending my Roman Catholic grammar school.

I was taught in one of the many religion classes that God was all powerful and all knowing and so forth and so on. Within the atmosphere of my Catholic grammar school a curious question arose — If God is all powerful then could God create a stone that even He (or She) could not pick up? If God was all powerful then the answer would have to be, “Yes, God could create a stone that even He or She could not lift.” However, once such a stone was created, God would no longer be all powerful because He or She would be powerless to lift that stone. Middle-school-aged children (6th, 7th and 8th graders) enjoy taking what is being taught and turning that information into something that will contradict, challenge, confuse or obfuscate the teacher. I have no recollection of how this paradox was resolved but I clearly remember that I could not let this question go until I had a satisfactory answer.

At some point I formulated my answer to this question. “Yes,” I thought, “God could create a stone that even God could not lift. He or She merely chose not to do so.” God has free will. I was satisfied with this understanding and left it as a settled matter needing no more consideration. The notion that the all powerful God, who is also all knowing, has free will, which He or She exercises constantly, would prove critical to my understanding of God and vital to understanding The Divine Paradox.

The knowledge of which I speak is encapsulated in language. I allow for the possibility of other knowledge that is not encapsulated in language. This non-encapsulated knowledge I leave aside for later consideration.

Language Sets

Language sets are systems of descriptions (expressions) of perceptions of reality.

As a teacher, I once taught a unit from a program known as Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) designed by Stan Progrov out of the University of Arizona. Daily lessons were structured in two parts. The first part was a round table discussion in which the teacher used a Socratic questioning approach to set up and develop necessary prerequisites for the students to engage the second part of the lesson. The second part of the lesson was a computer simulation or game which presented a problem to be solved by the students. I found this program (HOTS) to be enjoyable and enlightening as well as beneficial to my particular students, but that is not the issue at hand.

One of the units of HOTS was the challenge to successfully fly a hot air balloon culminating with the students’ defeat of the computer in a race across the computer’s monitor. To be successful the students had to adjust their thinking to align it correctly within two language sets. One language set consisted of the words: up, down, left, and right. This language set could describe the movement of the image of the hot air balloon traveling across the monitor. The other language set consisted of the terms relating to navigation: north, south, east, west, southwest, northeast, etcetera, as well as: altitude, ascending and descending. The discovery and use of gages was also necessary and critical.

The quandary for these students at the beginning proved to be their propensity to use the language set: up, down, left, and right in creating a strategy to fly their balloons. This language set did not carry all the knowledge needed to successfully complete the challenge. Movement of the image of the balloon across the screen was controlled by the balloon’s altitude which was indicated by the altimeter gage. Students did not succeed until they substituted the language set of navigational terms for the more generic language set of “up, down, left and right.”